Modeling Game Mechanics for Scalability

When you’re building a game, it’s tempting to model your server code directly after the player’s experience, especially for progression-based mechanics. But costly problems lurk within.

Consider a hypothetical role-playing game that rewards players for earning experience points and for completing tasks every day for a week. You might build two systems: one system that levels up players the moment that they earn enough experience points for a reward and another system (or use a cron job) that checks your player’s progress on daily tasks each day at midnight.

Though it’s easy to reason about these two systems, it’s likely that your game will get additional systems over time. That’s when this approach rears its ugly head: it explodes costs, breeds complexity, and hides fragility.

It’s costly because processing increases linearly with every new player. Your nightly cron job will take longer and longer to complete, or require additional, expensive computing power to run it fast enough, to say nothing of the nightly load bogging down your server.

It’s complex because you have to build a new system for each new mechanic, timer, or event. Your level progression system can’t easily reuse code from your daily tasks system and vice versa.

It’s fragile because you can tie your server code to the clock. If you don’t complete that daily progress check at midnight, gameplay can break or require a late-night rescue operation. What’s worse is that some periodic systems can become completely untenable, such as constant drain or accumulation of player resources. That cron job can’t reasonably run for every player, every second.

So what’s a game developer to do?

A way out of the naïve approach: player-driven processing

The good news is that there’s a way to model server code in a generalized way that works for many game systems: react to player events—such as logins, logouts, ending matches, and so on—as they happen.

Instead of periodically checking for changes that might apply to a given player, team, or item, wait for and respond to events that have truly happened. In some ways, this is like the event-driven programming paradigm: the server acts like a main loop that triggers callback functions.

This approach can reduce your server costs, minimize complexity, and make your game more robust because:

- Progression code runs on the server only when it directly affects a player.

- Server load is more evenly distributed in time.

- Event handling happens close in time to player activity, instead of waiting on scheduled cron jobs.

- Progression code can be more easily reused between game mechanics.

Let’s look at a high-level outline of this approach, then look at a real-world example.

An implementation pattern: progression templates

One pattern for implementing this model works in three parts:

- Define a static progression: write a template that defines milestones, rewards, and defaults for the system’s progress.

- Start the progression: when a progression begins, copy the template to the player’s data.

- Update on player action: every time a relevant event happens, update the player’s copy of the progression.

Implementing daily streaks with templates and event handling

Let’s look at an example: in our hypothetical game, we want to reward players who log in to the game on consecutive days. If the player logs in at least once every 24 hours seven times, they’ll receive a finishing reward, plus a smaller reward on the third day.

To set this up, we’ll create a static progression template in JSON format (JSON is just one option here—you might use a different format or data structure, but the concept still applies):

{

"title":"7-day check-in challenge",

"progress":0,

"next_login_after":"1602092170",

"rewards": [

{}, {},

{ "gold":300 },

{}, {}, {},

{

"gold":1000,

"items":[

"item374"

]

}

]

}

Whenever a player logs, we run some code for that player to find out if they have an active streak. If they don’t have an active streak (or their existing streak has been broken), we’ll copy the template to that player’s data:

function onLoginEvent(player)

if (player.streak == undefined or streakIsExpired(player.streak))

player.streak = copyNewStreakFromTemplate()

If the player already has an active streak and they’ve logged in at the right time, we can advance them through the unlocks in their streak:

if (time.now() > next_login_after and time.now() < next_login_after + ONE_DAY)

player.streak.progress += 1

awardUnlock(player, player.streak.rewards[player.streak.progress])

setTimeForNextUnlock(player.streak)

If we get to the end of a streak, we’ll need some additional logic to start again (more sophisticated templates might support a multiplier and reiterate the streak).

Other events might trigger actions against the streak, too. For example, a player might have the choice to cancel a streak (perhaps to start on some other progression). This would have its own event handler.

Event hooks in LayerG

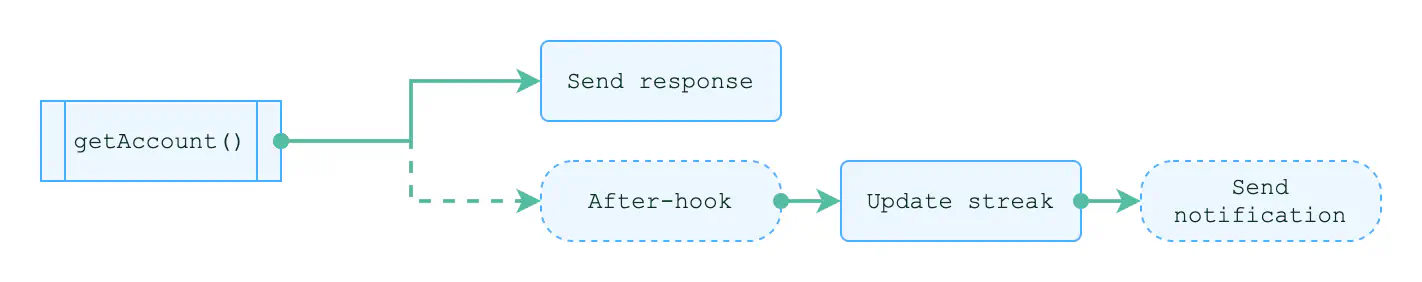

In LayerG, we can implement this pattern with after hooks. You can register a function that executes after each message received by the server. In that function, you can dispatch to more specific event handlers to level up players, award trophies, or, in this example, update a streak.

In this case, you can write an after hook that updates the player’s streak progression whenever a client calls the getAccount() function that sends an out-of-band notification about the streak.

After hook updating a player’s streak progression when getAccount function is called

In this case, we get an event trigger on an API that LayerG already provides and that you’re likely to use anyway: getAccount(). On the client side, there’s no additional code needed to trigger a streak update.

One pattern, many applications

This approach works for lots of progression-style game mechanics, including:

- Levelling up players, NPCs, and items

- Resource consumption and renewal, such as item degradation and energy recharge

- Challenges, quests, and achievements

- Retention incentives, such as streaks and daily rewards

Spare yourself the heartache of the never-ending cron job and consider modeling your game mechanics with events in mind.

Learn more

Learn to register a hook with LayerG

Related Pages